Table des matières

La cuisine moléculaire

L'alimentation serait à l'origine de nos capacités neuronales plus importantes : cf. Suzana Herculano-Houzel’s TED talk

Situations d'apprentissage

- la mayonnaise ratée

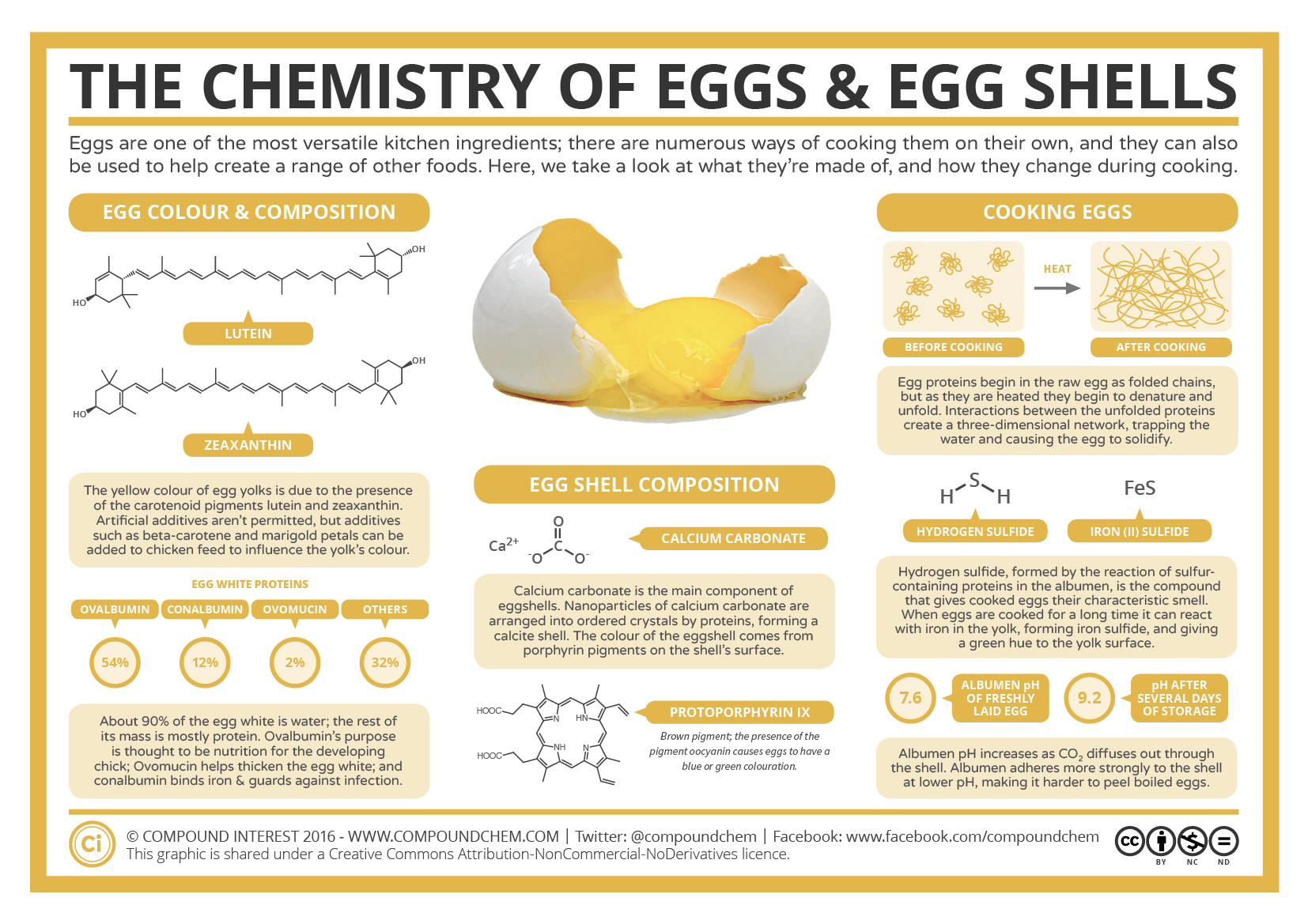

- l'œuf est très souvent trop cuit :

- le jaune devient verdâtre

- le jaune est trop sec

- le blanc est élastique

- il y a une odeur d'H2S

- enlever les écailles provoque l'enlèvement de morceaux de blanc, donc un aspect irrégulier, des traces d'ongles,…

- Comment centrer le jaune d'œuf. Quelle est sa position normale (= problème de densité) : dans un oeuf cru frais, le jaune “flotte” grâce aux chalazes, mais après quelques jours, les bactéries abîment ces tissus et je jaune se met en position haute dans l'œuf. Pour centrer le jaune à la cuisson, il suffit donc de retourner constamment l'œuf pendant la cuisson.

- la mousse au chocolat trop dure, trop riche

Des expériences

- La cuisson de l'œuf à froid avec de l'alcool : dénaturation et coagulation des protéines, on obtient des œufs brouillés à froid (3 minutes à 25°C), sans cuisson ! Essayez avec le jaune, et c'est pareil avec le blanc ! (explication : les molécules de protéines se déplient lors de la cuisson, s'accrochent et coagulent. L'alcool ou la chaleur permet d'y arriver. Un acide (citron) aussi. C'est aussi le cas pour l'action du citron sur le poisson qui contient de l'albumine.

- cocktail porto flip : jaune d'œuf + cognac + porto

- Cuisson de l'oeuf idéale à environ 75°C (1/2 heure) plutôt que 100°C (10 min) ! N.B. 1 g d'eau liquide est susceptible de donner 1 L de vapeur à la pression atmosphérique, et donc une cuisson à 100°C est susceptible de créer une augmentation excessive de la pression provoquant des éclatements. Et les “trucs” consistant à ajouter du sel ou du vinaigre n'arrange rien à cela ! Et de toute façon, l'œuf est surcuit si on le chauffe à 100°C.

- Cuisson et maintien à 64, 65, 66°C ! Un œuf mollet peut être maintenu dans cet état en le plaçant à 65 °C.

- fabriquer des œufs cubiques : le traiter 5-6 min à 65°C, l'écailler, et ensuite le placer dans un moule cubique et poursuivre la cuisson à 75°C.

- Utilisation d'agar-agar = algue rouge (E407) additif naturel (caragenane ?) pour donner du moelleux mais sans gélifier (exemple d'utilisation : les “danettes”).

- Spaghetti de fruit : utiliser une seringue à catheter et un tube. Ajouter 0.8g d'agar-agar dans 100g de préparation bouillie, laisser refroidir. Faire un spaghetti dans une cuillère. Autres exemples :

- spaghetti de tomate avec mozzarella et feuille de basilic.

- Mousse de fromage entourée de spaghetti de concombre dans une boule en plastique (hémisphères)

- !! nécessité d'une balance précise. Il faut par exemple 0.455% d'agar-agar dans le lait.

- Alginate de sodium : ajouter petit à petit 08.g dans du sirop de menthe (–> solution limpide fluide). Préparer un bain de calcium (eau riche en Ca, complément alimentaire). Déposer des gouttes dans l'eau. On obtient des billes “caviar” de menthe. Les repêcher avec une passoire pour les placer dans du Kir o de l'eau. Lorsqu'on écrase en bouche, le sirop est libéré ! Avec du gin tonic (contenant de la quinine), on a un effet phosphorescent dans le cocktail. Les billes ne sont pas stables et ne tiennent pas longtemps…

- Possibilité de faire tenir un liquide dans une coque de gélatine (pour la manger) :

- extraction de la pectine (cf. confitures). Faire bouillir très longtemps (6h) une clémentine entière (rmq, l'évaporation des esters odorants font évidemment perdre du goût). Ajouter à cette pectine de l'eau riche en Ca. On obtient une marmelade instantanée, sans sucre ajouté.

- myrtille/cassis (fruits rouges), on obtient un liquide noir (la couleur dépend de l'acidité). Des fruits cuits dans une eau riche en bicarbonate –> coulis de fruits noir. Ajout de jus de citron (acide) concentré –> dégagement CO2 + “rougissement” des fruits. Po

- Myrtille centrifugée + sucre + bicarbonate –> couleur noire. Ajout d'acide –> dégagement de CO2, couleur rouge et effervescence !

- avantage agar-agar sur gélatine : celle-ci peut être détruite par les enzymes de fruits

- Si la proportion agar-agar est pas bonne (trop liquide ou trop dur) : faire rebouillir, ajouter eau ou agar-agar…

Aspects scientifiques et techniques

Les goûts et textures

influencées par les réactions (Maillard), l'acidité, le sucre, l'amertume,…

Textures influencées par la structure moléculaire

- Émulsion (mayonnaise)

- mousse (blancs en neige)

- gel

- combinaisons de ces structures de base

- l'utilisation d'azote liquide

- …

Une émulsion gélifiée permet par exemple d'avoir de la vinaigrette en tranche ! (utilisation d'agar-agar ?)

Alternative à la recette classique de mousse au chocolat (faire blanchir des jaunes et du sucre, ajouter du chocolat fondu avec du beurre, puis les blancs : délicat et calorique !) :

- il faut réaliser une émulsion mousseuse ! (cas aussi de la chantilly)

- utiliser un siphon

- moitié chocolat, moitié eau (utilisation d'agar-agar ?)

- fondre dans une casserole (émulsion stable)

- 2 cartouches (?) de gaz (N2O gaz hilarant soluble dans les aliments, yc graisses ?) + siphon

- placer au frigo (refroidissement + solubilisation du gaz, sous pression)

- actionner le siphon –> mousse non sucrée (on peut en ajouter si souhaité), légère

- Recette analogue :

- monbazillac + foie gras + siphon –> mousse

- si les mousses sont placées dans de l'azote liquide, on les surgèle instantanément en surface. Analogue d'un sorbet croquant avec du moelleux dans le coeur !

- What’s cooking? Martina Hestericova, Neil Goalby, 22 January 2020, Understand the chemistry behind the colour changes in food

Café

- Café congelé en boule : placer du café dans une baudruche, la faire surnager en la tournant sur de l'azote liquide. Lorsque le café est congelé, casser le ballon –> boule de café givré (trouer ?)

- extraction du café : Systematically Improving Espresso: Insights from Mathematical Modeling and Experiment Cameron, Michael I. et al., Matter january 22, 2020, DOI: 10.1016/j.matt.2019.12.019 → Maths says you need coarser coffee grounds to make a perfect espresso New Scientist, 2020

La mayonnaise

- Snippet de Wikipédia: Mayonnaise

La mayonnaise est une sauce froide à base d'huile émulsionnée dans un mélange de jaune d'œuf et de vinaigre ou de jus de citron. L'ajout de moutarde en fait une rémoulade, qui en est un ancêtre. Cependant, à l'usage, le terme « mayonnaise » a remplacé le terme « rémoulade », même quand la mayonnaise est préparée à base de moutarde. La première recette similaire à la recette moderne a été publiée par Marie-Antoine Carême.

le jaune d'œuf contient des composés tensioactifs (protéines, phospholipides), qui permettent de réaliser une émulsion de l'huile dans l'eau. Ces molécules “amphiphiles” peuvent se modéliser comme des bâtonnets avec une hampe lipophile (forte affinité pour les huiles et graisses) (hydrophobe) et une tête hydrophile (forte affinité pour l'eau). L'émulsion se forme avec une grande quantité de micro-domaines (gouttelettes microscopiques d'huile) contenus dans la phase aqueuse continue (vinaigre). L'émulsion est stable grâce aux molécules amphiphiles du jaune d'œuf.

Pour rattraper une mayonnaise ratée (l'émulsion d'huile dans l'eau ne s'est pas faite), il s'agit donc de recommencer avec une petite quantité d'huile en présence de la phase aqueuse et des molécules amphiphiles pour créer l'émulsion, et ensuite rajouter progressivement la préparation ratée tout en mélangeant vigoureusement pour maintenir l'émulsion.

La brandade de morue, une autre émulsion

- recettes :

Cuisson des pommes de terre

-

- article en français : Les mathématiques pour faire les meilleurs pommes de terre

Crème glacée

- La crème glacée est une émulsion eau/matière grasse (environ 10%) congelée avec des bulles d'air, 30-50% du volume totale de la glace (c'est aussi une mousse)

- Le sirop de glucose permet de garder un aspect moelleux de la glace et empêcher un durcissement trop important

- Défi technique de la glace : garder saveur et souplesse. Lors de la congélation ❄️ (choc T°C)

- Les matières grasses s’agglutinent

- les bulles d’air incorporées à la confection se dispersent

- les molécules d’eau se cristallisent en paillettes rendant la glace granuleuse

- Le froid a tendance à engourdir les papilles gustatives, les rendant moins sensibles. Il faut donc ajouter du sucre (en plus du lactose du lait) pour produire l’effet souhaité aux basses températures auxquelles la crème glacée est habituellement servie.

- La crème glacée a bon goût à cause de sa teneur élevée en graisse. La crème glacée doit contenir au moins 10% de matière grasse venant du lait. Les meilleures glaces contiennent jusqu'à 20% de MG. Dans un produit ultratransformé, de mauvaise qualité, c'est de la graisse végétale

- La graisse (apolaire) se mélange mal avec l'eau (polaire). On a recours à des stabilisants (qui empêchent la formation de gros cristaux de glace) et des émulsifiants (stabilisent l'émulsion), d'où les nombreux additifs des crèmes glacées commerciales “industrielles”

- The Chemistry of Ice Cream – Components, Structure, & Flavour Compound Interest, 2015

Références :

- https://twitter.com/T_Fiolet/status/1149373302684749825 (petit thread twitter)

- The Ice Cream eBook, Professor H. Douglas Goff, University of Guelph, Canada

- Chris Clarke, The Science of Ice Cream (Royal Society of Chemistry, 2004) DOI: 10.1039/9781847552150 ISBN: 9781847552150

Les nouvelles techniques

- le bain de calcium (?)

- la quinine fluorescente

- le contrôle des températures, la

- le siphon et utilisation du protoxyde d'azote ou oxyde nitreux

- la pectine, le bicarbonate

- la notion de conteneur alimentaire mangeable

Cuissons alternatives

-

- cuire à basse température (50-60°c) la viande dans son emballage avant de la griller

- https://mobile.twitter.com/brusicor02/status/1372604699661193219 (top chef 2021 saison 12 épisode 6) : la cuisson à l'aide d'acétate de sodium

- …

Les ustensiles, le matériel de cuisine

Confitures et casseroles

Jadis, il était recommandé de préparer ses confitures dans des casseroles en cuivre, mais pas en cuivre étamé (recouvert d'une couche d'étain destiné à prévenir l'apparition dans certaines conditions de vert-de-gris, toxique), surtout pour les fruits rouges. Actuellement, les confitures sont préparées dans des récipients en acier inoxydable. Qu'en est-il ? quels sont les avantages et inconvénients ?

Hervé This rapporte ou propose quelques expériences :

- mettre en présence de l'étain (propre, métallique) et des fruits rouges : rien ne se passe

- mettre en présence du cuivre (propre, métallique) et des fruits rouges : rien ne se passe

- dépôt de sels d’aluminium sur des framboises écrasées : elles blanchissent

- dépôt de sels de cuivre : elles prennent une belle couleur orangée

- avec certains sels d’étain, les framboisent prennent une teinte violette intense (immangeable)

Conclusion : Il n’est pas grave de mettre des framboises dans de l’étain bien propre. il n'en va pas de même avec de l'étain oxydé ou des sels d'étain.

Utilité du cuivre : si on écrase des framboises dans une bassine en cuivre et qu'on les y laisse une heure ou deux, on observe après avoir enlevé les framboises que le cuivre est mis à nu : il y avait en fait une mince couche d'oxyde de cuivre qui s’est dissous dans le jus de framboises. Quel est l'effet de cet oxyde sur la préparation des confitures ? Plusieurs informations et versions circulent. Certains avancent que les ions cuivre sont un excellent fongicide (certains ajoutent du sulfate de cuivre dans leur piscine pour éviter la prolifération d'algues). Hervé This propose une autre expérience simple :

Dans deux récipients en verre, vous disposez des rondelles d’orange, un petit verre d’eau et du sucre (autant de sucre que de fruits plus eau). Dans un des récipients, vous ajoutez du sulfate de cuivre, que vous aurez acheté chez le droguiste. Cuisez les deux confitures, le même temps, laissez refroidir et comparez : la confiture bleuie par le sulfate de cuivre est dure, alors que l’autre reste coulante. En effet, la cuisson des fruits a libéré les molécules de pectine des fruits, et le cuivre a réuni ces molécules, formant un réseau qui piège l’eau et les fruits. Autrement dit, le cuivre a favorisé la prise des confitures.

Autres additifs utilisés pour les confitures : acide salicylique (pour améliorer la conservation après préparation dans les casseroles en acier inoxydable), citrate de calcium (acidifiant et effet raffermissant du calcium). L'oxyde de cuivre en trop grande quantité est nocif et provoque vomissements et diarrhées chez l'homme.

Références :

Appareillages avec régulation thermique

- ANOVA Precision Cooker (environ 120 EUR, régulation à 0.1°C près, cf. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.jchemed.8b00163), exemple d'utilisation http://zewoc.com/premier-anova-precision-cooker/

Additifs alimentaires

- sites généraux :

- https://www.additifs-alimentaires.net/index.php (site web orienté “bio”

- divers

Antioxydants

Arômes et goûts

- Arôme artificiel vanille : la vanilline qui donne son bon goût à la vanille n'est pas présente dans les grains noirs. Bien souvent on laisse ces grains, voire on les rajoute dans des glaces avec de la vanilline synthétique pour donner une impression de qualité. Le goût de la vanille provient de l'enveloppe de la gousse de vanille ainsi que de la pulpe, et le goût naturel ne vient pas que de la vanilline, c'est pour cela qu'il est si subtil et que l'on le peut différencier du goût artificiel. La vanilline pure a un goût fort et acre si prise seule et trop concentrée. En aromatisation artificielle on peut aussi utiliser de l'éthylvanilline encore plus forte et plus éloignée de l'arôme naturel ! Puis on ajoute les fameux grains noirs issus de gousses épuisées dont on a extrait l’arôme naturel pour d'autres usages. N.B. : l'arôme artificiel vanille est parfois complété par un extrait naturel, le castoréum, une sécrétion huileuse et odorante produite par des glandes de castors, glandes s'ouvrant dans le cloaque de l'animal, près du pénis et de l'anus.

- Arôme artificiel d'amande : benzaldéhyde.

Colorants

- rouge carmin :

conservateurs

Édulcorants

Thé et infusions

- questions concernant la température, l'oxygène dissout, le CO2,…

Régimes et comportements alimentaires

- La "détox", c'est de l'intox, Florian Gouthière (Rédigé le 15/11/2013, mis à jour le 27/12/2018)

Aliments et toxicité

- Noyaux de pêches et cyanure, l'acide cyanhydrique des amandes de fruits (vérifier)

- Pommes de terre (pelures) : la pelure (ou les 3 premiers millimètres sous la surface, à vérifier) contient des glycoalcaloïdes toxiques qui ne sont pas détruits par la cuisson (sauf partiellement à 170°C) : chaconine, solanine, solanidine, et autres. Ces substances sont surtout présentes dans les pdt vertes, germées ou abîmées. Des références proposées par Hervé This (fixme - DOIs et liens) :

- Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 41 (2005) 66–72Potato glycoalkaloids and adverse eVects in humans: an ascending dose study, par Tjeert T. Mensinga et al.

- Perishables Handling Newsletter Issue No. 87, August 06, A Review of Important Facts about Potato Glycoalkaloids by Marita Cantwell

- Current Research in Nutrition and Food Science, A Review of Occurrence of Glycoalkaloids in Potato and Potato Products DUKE GEKONGE OMAYIO et al

- conine : poison de la cigüe

- saffrole : poison de la noix muscade

- ammanitoidine : poison de l'ammanite phalloïde

- hyoscyamine : alcaloïde

- scopolamine

- atropine : poison issu du datura

- …

Aliments alternatifs

- Viande de synthèse

- À base d'insectes

- Possibilities for Engineered Insect Tissue as a Food Source Natalie R. Rubio, Kyle D. Fish, Barry A. Trimmer and David L. Kaplan, Front. Sustain. Food Syst., 17 April 2019 DOI: 10.3389/fsufs.2019.00024

Voir aussi ...

- How to make an INSIDE OUT boiled egg

- La fermentation lactique, utilisée pour la choucroute, mais pas que !

- Les aliments transformés ou « ultra-transformés »

- Quoi dans mon assiette, Actualités en sciences, alimentation et santé – Uniquement basé sur des publications scientifiques

Ressources didactiques

MOOC:

Articles :

- Molecular gastronomy in the chemistry classroom, Johanna Dittmar, Christian Zowada, Shuichi Yamashita, Ingo Eilks, science in school issue 36 summer 2016. L'article montre comment faire des bulles d'alginate et présente trois expériences en exemple, chacune pouvant être effectuée en une période : une réaction acide-base, la chimio-luminescence avec redox, et la convection thermique avec un effet thermochromique.

- Fiches Science & Cuisine. URLs :

Pagailles et aberrations en cuisine

Par exemple :

- ma mayonnaise est ratée, comment la récupérer ? (molécules amphiphiles et émulsion)

- le beurre est rance, je n'ai que lui, comment faire ? (réactions acide-base et élimination des ions butyrate)

- j'ai mis trop de sel dans une préparation, comment en enlever ? (osmose)

- je dois préparer de la crème glacée, et je ne dispose que de glaçons (abaissement cryoscopique)

- je n'ai que 3 œufs, et ma recette en demande 4 (règle de trois, proportions)

- j'ai oublié d'acheter du “PEC” pour faire ma confiture de fraise (pectine des pommes)

- mes avocats ne sont pas mûrs, et je dois prépare un repas pour dans deux jours, que faire (température et catalyse → cinétique)

- verser un filet d’huile d’olive dans l’eau des pâtes : en quoi serait-ce utile ?

- cuire vos œufs durs avec un filet de vinaigre de vin ou une petite pincée de sel, ça marche ?

- plonger les légumes dans une eau glacée pour fixer la chlorophylle. Est-ce vrai ?

La mayonnaise

- utiliser uniquement de l'eau, du jaune d'œuf et de l'huile avec un fouet ou un batteur pour préparer de la mayonnaise. On peut utiliser seulement 1 mL de jaune. Montrer qu'en ajoutant trop d'huile, on peut “rater” la mayonnaise, c'est à dire ne plus avoir systématiquement l'émulsion de l'huile dans l'eau. Utiliser un microscope pour montrer que la mayonnaise correcte est formée de petites gouttes d'huile dans une phase aqueuse continue.

- Pour “rattraper” une mayonnaise, il faut donc la considérer comme de l'huile “continue”, et l'utiliser ainsi en l'ajoutant lentement à l'émulsion initialement créée, en fouettant intensivement.

Expériences scientifiques avec des aliments

- Propriétés osmométriques des la membrane des œufs, laissant passer des petites molécules (diiode,…), mais pas des grandes (amidon,…)

- vinaigre et lait → galalithe ou pierre de lait

- Analyses sur les champignons : Natural experiments: chemistry with mushrooms → protéines, vitamine C, potassium et sodium, ions phosphate, ions chlorure

- Coloration de pâtes en utilisant du jus de chou rouge et du bicarbonate : http://www.sewhistorically.com/homemade-all-natural-blue-pasta/

- Transformer des olives vertes en olives noires, sur base de ces références

- thread critique sur twitter (version "Thread reader") avec la référence Producing Table Olives de Stan Kailis, David Harris

- expérience : olives vertes, hydroxyde de sodium ou potassium, sel, gluconate de fer,…

- …

Étymologie

-

- Fruit voyageur : le mot abricot vient du catalan albercoc, emprunt à l'arabe al-barqūq, qui vient du grec byzantin βερικοκκία, descendant du grec ancien πραικόκιον “abricot”, lui-même emprunté au latin praecocia “pèches précoces”, pluriel de praecoquum (malum) “(fruit) précoce”

- Le mot latin est un composé de prae- “avant”, et -coquus “mûr, prêt à consommer”, qui vient du verbe coquo qui a le double sens de “mûrir” et “cuisiner = rendre consommable”, et qui donne par exemple le français “cuire”, et qui a été emprunté en germanique, d'où l'anglais “cook”

- Le participe passé de coquo “cuire, cuisiner”, coctus, est à l'origine du français “cuit”, et “biscuit” = “cuit deux fois”, ainsi que du mot “biscotte”, emprunté à l'italien biscotto, qui a le même sens et la même origine.

- Le mot latin coquus “cuisinier”, est également à l'origine du français maître-queux = “cuisinier”, et de sa variante “maître-coq”, influencée par l'anglais “cook”.

- Le mot “cuisine” vient lui du latin coquina, dérivé de coquus, qui donne le mot cuisine dans toutes les langues romanes, par exemple l'espagnol cocina, d'où l'arabe marocain kuzina ; il a été emprunté en celt. = breton kegin, en germ., anglais kitchen (d'où le japonais kichin!)

- On le trouve jusque dans le hongrois konyha “cuisine”, via les langues slaves, comme le russe kuxnja, le tchèque kuchyně… C'est aussi l'origine de l'allemand Küche, du finnois kyökki, emprunté au suédois kök : Le mot coquina “cuisine” a vraiment fait le tour du monde !

- Mais la racine de ce mot se trouvait déjà dans nombre de ces langues, car il s'agit d'une racine indo-européenne attestée *pekʷ- “mûrir / cuisiner”, qui donne par exemple le nom du four dans les langues slaves (russe pečʹ “four”), le sanskrit pácati, le grec πέσσω “cuisiner”…

- La racine *pekʷ- “cuire, mûrir” donne aussi le grec πέψις “digestion”, dont dérive le nom d'une enzyme, la pepsine, qui favorise la décomposition des protéines en acides aminés. Le mot abricot est donc étymologiquement apparenté au mot Pepsi.

- La plus ancienne attestation de cette racine se trouve en linéaire B, l'écriture du grec mycénien, sur les tablettes de Pylos (vers 1450 avant J.C.), avec la forme 𐀀𐀵𐀡𐀦 (a-to-po-qo), qui doit signifier “boulangers” et correspond au grec ancien (1000 ans plus tard!) ἀρτοκόπος

Histoire et alimentation

- Citoyens à vos assiettes ! Les grands mythes de la gastronomie, Université de Liège

- Les grands mythes de la gastronomie : Parmentier et la pomme de terre (diffusé le 10 juin 2018)

- Les épices et la viande avariée (diffusé le 13 mai 2018)

- La tarte des sœurs Tatin (diffusé le 15 avril 2018)

- L'histoire du pain levé (diffusé le 18 mars 2018)

- L'histoire du restaurant (diffusé le 18 février 2018)

- Le croissant du siège de Vienne (diffusé le 21 janvier 2018)

- Une petite histoire de la pizza (23 juin 2019)

- le boulet liégeois (28 avril 2019) → avec le mythe de la sauce de “madame Lapin” !

- Le Hochepot gantois (ou hochepot flamand) (31 mars 2019)

- Marco Polo, les pâtes et Hollywood (3 mars 2019)

- L'histoire vraie de la pomme de terre frite ( 3 février 2019)

- Aux origines de la mayonnaise (16 décembre 2018)

- L'étonnante histoire de la fourchette (18 novembre 2018)

- Napoléon et le poulet Marengo (14 octobre 2018 )

- L'invention de la crème Chantilly (16 septembre 2018)

Références

- Portail Alimentation et gastronomie de Wikipédia

-

- Un chimiste en cuisine, préface de Thierry Marx. Raphaël Haumont, Dunod 2013 - 184 pages - EAN13 : 9782100702084

- Répertoire de la Cuisine Innovante, Thierry Marx et Raphaël Haumont. Edition Flammarion, 2012, ISBN : 978-2-08-127805-9

- Centre Français d’Innovation Culinaire (CFIC), Université de Paris Sud

-

- cours du master 2 “Food innovation and product design”

- Ces aberrations culinaires qui se transmettent de génération en génération, Le Figaro, Le 10 mai 2017

- Discovering the Chemical Elements in Food Antonio Joaquín Franco-Mariscal J. Chem. Educ., 2018, 95 (3), pp 403–409 DOI: 10.1021/acs.jchemed.7b00218

- MOOCs

- Science & Cooking: From Haute Cuisine to Soft Matter Science (part 1), Top chefs and Harvard researchers explore how everyday cooking and haute cuisine can illuminate basic principles in physics and engineering.

- Gourmet Lab: The Scientific Principles Behind Your Favorite Foods, NSTA, 2011 By: Sarah Young

- Chemistry of Cooking, A Course for Non-Science Majors Chapter (Book) Jason K. Vohs, Chapter 3, pp 23–35 DOI: 10.1021/bk-2013-1130.ch003 in Using Food To Stimulate Interest in the Chemistry Classroom, Editor(s): Keith Symcox, Volume 1130, 2013, American Chemical Society ISBN13: 9780841228184 eISBN: 9780841228191 DOI: 10.1021/bk-2013-1130

- Le Grand Livre de notre alimentation Avec 25 experts de l'Académie d'agriculture de France éditions Odile Jacob, 2019, EAN13: 9782738147974

Matériel :

Aliments :

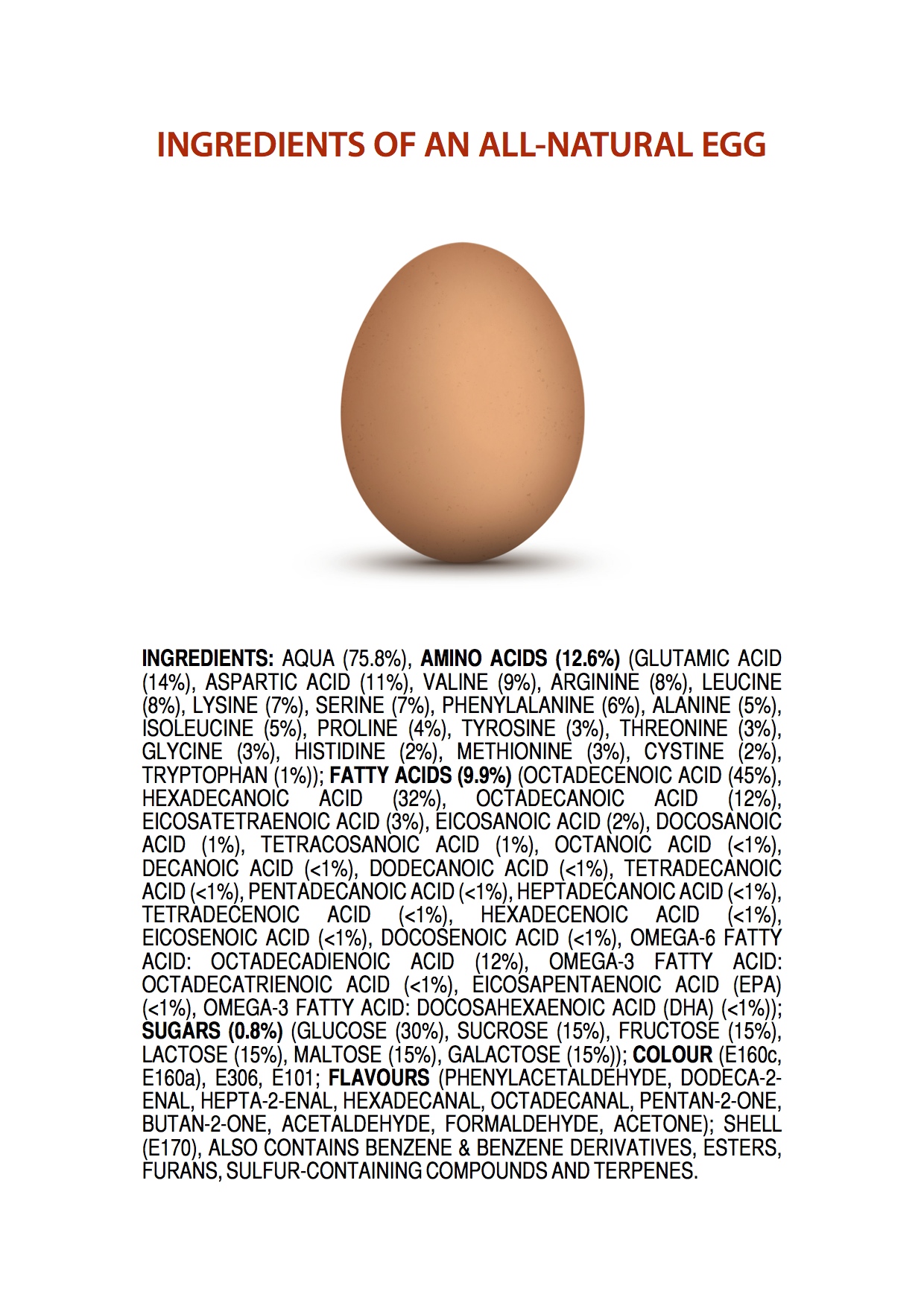

- The "Ingredients" in Organic, All-Natural, Fruits & Eggs Are Not What You'd Expect : la composition “chimique” d'aliments “naturels” ou un regard de chimiste sur nos aliments de base. Cf aussi les sources sur le Blog de James Kennedy et d'autres articles sur Food Hacks Daily.

- Open Food Facts - France, cf. Open Food Facts - openfoodfacts : base de données libre et ouverte sur les produits alimentaires (données, scores nutritionnels, illustrations téléversées)

- Nutriscore

- Novascore

Additifs alimentaires :

- Additif alimentaire sur Wikipédia

- Liste des additif alimentaire sur Wikipédia

- Quels sont les additifs alimentaires à bannir ? (podcast France-Culture, en partenariat avec Le Monde)

- Additifs alimentaires, sur belgium.be, site belge d'informations et services officiels

- Additifs alimentaires, sur le site de l'EFSA (autorité européenne de sécurité des aliments)

- Additifs alimentaires, sur le site officiel canadien canada.ca

- http://www.additifs-alimentaires.net/additifs.php (site web de type personnel)

- http://www.les-additifs-alimentaires.com/ (site web de type personnel)

- avantage annoncé d'absence d'additifs : https://twitter.com/toutsurlabio/status/1179376104974557185 (campagne anxiogène et nombreuses substances naturelles, également utilisées en AB, anodines,…)

Divers :

- Soft matter food physics—the physics of food and cooking Thomas A Vilgis 2015 Rep. Prog. Phys. 78 124602 DOI: 10.1088/0034-4885/78/12/124602

Définitions :

- sucres - glucides

- sucres rapides : monosaccharides (glucose, fructose), disaccharide (saccharose ou sucrose)

- sucres lebts : polysaccharides (amidon)

- Glycogène

- graisses - lipides

- …

- protides

- acides aminés

- peptides

- protéines

Exemple d'informations sur l'œuf

- Snippet de Wikipédia: Eggs as food

Humans and other hominids have consumed eggs for millions of years. The most widely consumed eggs are those of fowl, especially chickens. People in Southeast Asia began harvesting chicken eggs for food by 1500 BCE. Eggs of other birds, such as ducks and ostriches, are eaten regularly but much less commonly than those of chickens. People may also eat the eggs of reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Fish eggs consumed as food are known as roe or caviar.

Hens and other egg-laying creatures are raised throughout the world, and mass production of chicken eggs is a global industry. In 2009, an estimated 62.1 million metric tons of eggs were produced worldwide from a total laying flock of approximately 6.4 billion hens. There are issues of regional variation in demand and expectation, as well as current debates concerning methods of mass production. In 2012, the European Union banned battery husbandry of chickens.

- Snippet de Wikipédia: Œuf (aliment)

L’œuf, en tant qu'aliment, est un produit agricole issu d'élevages divers et utilisé par les humains comme nourriture simple ou pour servir d'ingrédient dans la composition de nombreux plats dans la plupart des cultures du monde.

Le plus utilisé est l’œuf de poule, mais les œufs d’autres oiseaux sont aussi consommés : caille, cane, oie, autruche, etc. Les œufs de poissons, comme le caviar, ou de certains reptiles, comme l'iguane vert, sont également consommés, toutefois leur utilisation est très différente de celle des œufs de volaille.

Les œufs du commerce utilisés en cuisine dans les pays industrialisés ne sont généralement pas fécondés, parce qu’ils proviennent le plus souvent d’élevages industriels où les coqs sont absents. Fécondés ou non, ils sont consommés ou cuisinés à l’état frais ; cependant, dans les usages culinaires asiatiques, les œufs sont parfois consommés couvés, comme le balut, ou mis à fermenter pendant plusieurs semaines, comme l’œuf de cent ans.

Compound Interest :

Ingredients of an All-Natural Egg, de James Kennedy, sur jameskennedymonash.wordpress.com

Références sur les œufs

- What's In An Egg? NSTA Daily Do - Wednesday, March 25, 2020 (expérience à la maison, pour mirer des œufs)

- Geometry-Induced Rigidity in Nonspherical Pressurized Elastic Shells A. Lazarus, H. C. B. Florijn, and P. M. Reis, Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 144301 – 2012 DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.144301

- blancs d'œufs, soufflés, meringues et loi des gaz :